You’ve heard the phrase “History Happened Here.” That is certainly true in areas of north-west Buffalo called “Black Rock Village” and “Conjockety Creek” and vicinity during the War of 1812. Today these communities are known as Scajaquada Creek, Buffalo’s Front Park, Grant Ferry, Forest, Buffalo State, Grant-Amherst and Black Rock neighborhoods. Nearly 200 years ago, War of 1812 history did happen here, and in a big way.

In those days, there was an enormous, actual black rock situated along the Niagara River at the foot of what is today School Street. Just north was Black Rock Village, centered at where Niagara and West Ferry Streets meet today. Prior to the breakout of the War of 1812, then-Congressman Peter B. Porter, whose house anchored the village and who would be a prominent figure in the local war effort, voted for increased military spending and demanded the passage of laws to strengthen the nation’s defense so the people of Western New York could “support with their persons and their property… the just rights of this country.”

The area known as the neighborhood of Black Rock today just north of Scajaquada Creek was sparsely occupied, but after the war it grew dramatically thanks in large part to development of the Erie Canal. (The actual black rock near School Street was blasted away during the canal’s construction.)

Once begun on June 18, 1812, the war lasted nearly three years, ending with the proclamation of the Treaty of Ghent by the U.S. on February 18, 1815. Many notable fortifications, battles and skirmishes and much destruction took place in and around Black Rock village and Scajaquada Creek. Historic figures and their stories are becoming better known as the 200th anniversary of the War of 1812 arrives next year and is commemorated through 2015, and this piece provides a primer on some of them.

Black Rock village and Scajaquada Creek’s contribution to the War of 1812 begins with providing worthy ships used by Commodore Oliver Hazard Perry to achieve victory in the September, 1813 Battle of Lake Erie. It was in this battle that he declared the immortal words, “We have met the enemy and they are ours.” At least three of the vessels that took part were prepared for service in the navy yard at Scajaquada Creek: Caledonia, Trippe, and Somers. They were refitted, turned into gunboats, and armed there. The resulting naval battle was so fierce, and the tragedy so great, that Perry insisted that surrender ceremonies be held on board the his recaptured U.S. Brig Lawrence, where many crew had been killed or wounded, so as to better allow the British to see the terrible price his men had paid.

Prior to that battle, in October, 1812 the HMS Brigs Detroit and Caledonia were captured by the Americans at the suggestion of the famous Seneca chief named Farmer’s Brother, with the Detroit running aground on Squaw Island. A drawing from an original sketch of this event, drawn by heralded naval officer Lt. Jesse D. Elliott as part of his report afterward to the Secretary of the Navy, serves as The Picture of Earlier Buffalo’s “second oldest view of Buffalo.”

In contrast, the war on land began inauspiciously for Black Rock, with “Bishopp’s Raid” on the naval repair yard and other installations at Scajaquada Creek occurring in July, 1813. A British force of 250 men rowed upriver from their base in Chippewa. The swift Niagara River current scattered the boats on our shore.

As a result, one group that did land on target proceeded as an advance guard and managed to scare off a sentry at the bridge crossing Scajaquada Creek, thereby facilitating the surprise and overwhelming of the entire American garrison at Black Rock without significant resistance. However, one incident highlighted the losses the war would bring to both sides of the conflict. As the British forces withdrew, an American counter-attack was launched on the boats departing for Canada, and Lt. Col. Bishopp (Bisshopp), a popular and able commander of British forces on the Niagara, was wounded, dying a few days later at age 30.

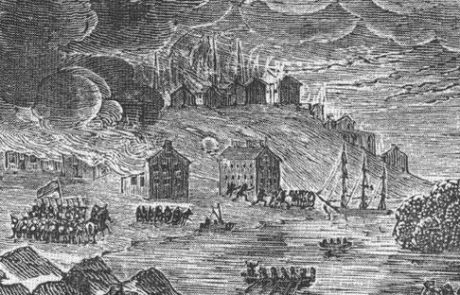

Perhaps better known is the Burning of Black Rock and Buffalo in late December, 1813, which was undertaken by British forces in retaliation for the American wintertime burning of the community of Niagara (now Niagara-on-the-Lake), which was done so that enemy troops could not encamp there and advance on Fort George, which was then under U.S. control. The enemy landed in the vicinity of the foot of Amherst Street. Local American militias responded, but suffered from disorganization, with the result that many more were killed from among the American forces than British and their Native American allies, and enemy pillaging of supplies and destruction of remaining defenses at Buffalo and Black Rock was devastating. Civilian homes at Black Rock and Buffalo were torched as well as nearby farms, leaving a wasteland of ashes behind when the British withdrew. Sarah Lovejoy, whose house was located on Main Street, was killed after her husband Joshua had gone to defend Black Rock. The daughter of a neighbor reported: “My mother saw an Indian pulling the curtains from the window of the Lovejoy house and saw Mrs. Lovejoy strike his hand with a carving knife and saw the Indian raise his hatchet.”

By August, 1814, as in the previous two attacks, the British again planned an attack where they would land below the Scajaquada Creek and then move south on Black Rock and Buffalo. However, this time an alert American commander, Major Lodowick Morgan, detected the British plan and placed a force of 240 men of the First Rifle Brigade and a small number of militia and volunteers into positions covering the main road to Buffalo. At the bridge where the British would have to cross the Scajaquada, located just west of Tops Market in Grant-Amherst in the present day, Americans tore up the floorboards so the British could not cross. Several attempts were made by the British troops under command of their officers to replace the floorboards, rush the bridge, and cross the river or outflank their counterparts, but each time the accurate fire of American riflemen drove them off, creating increasing casualties for the British until they finally retired to Squaw Island. Major Morgan became the “Hero of Conjockety” and the attack, which was aimed at Black Rock and Buffalo, was repulsed. This battle also known as the Battle of Scajaquada Creek Bridge was decisive for if it had been successful it would have disrupted U.S. occupation of Fort Erie. Occurring near the end of the War of 1812, our troops showed the ingenuity and steadfastness that has enabled us to secure our borders, ensure 200 years of peace with our Canadian neighbors, and make our country great.

Sources used include historical works published and unpublished, authored by Richard Feltoe, Pat Kavanaugh, Mark Goldman, Benson Lossing, Peter A. Porter, Joseph Grande, Lura Lincoln Cook, William Dorsheimer, and others. Compiled by Bill Parke on July 27, 2011. Revisions pending. Revisions: 6/3/11 Original Draft; 6/18/11 Revision adds PK’s 3 edits received 6/4/11; 6/29/11 adds Lt. Jesse D. Elliott as source of sketch; 7/27/11 actual black rock sited at School St. per S. Glasgow.