by Warren Glover

Charles Cecil Bisshopp was born in West Sussex, England in 1783 and joined the First Foot Grenadiers as an Ensign in March, 1799. One year later he was promoted to Lieutenant in his regiment, equal to Captain in the British Army. His rapid rise in rank can be partly attributed to his coming from a noble family with high connections in the civil service and the military.

During 1802 and 1803, he was earning 50 crowns per year and by 1811 he was a brevet-major, serving briefly with the 98th Foot Company. In 1801, he served as a private secretary to Rear Admiral Sir John Borlase Warren in St. Petersburg, Russia at the coronation of Czar Alexander I. By 1809, he served in the less successful expeditions in LaCorrum, Spain and Walcherea, the Netherlands. In 1811 and 1812, he represented the Newport region in Parliament. Appointed Inspecting Field Officer of Militia in April, 1812, he transferred at his request to British North America, becoming a brevet Lt. Colonel to experience a newly opened theater of operations. In the same year, Maj. Gen. Sir Roger Sheaffe placed Bisshopp in command of regular troops in the Niagara peninsula between Chippewa and Fort Erie. On November 28, 1812, Bisshopp’s regulars and militia repulsed two attacks by American Brig. Gen Alexander Smyth as part of his failed invasion of Upper Canada via the campaign at Frenchman’s Creek.

Following the American capture of Fort George on May 27, 1813, Bisshopp withdrew his forces to Burlington Heights to join with Brig. Gen. John Vincent in his retreat, under plans laid out by their High Command. Bisshopp was in charge of the 41st Regiment during the British victory in the Battle of Stoney Creek on June 6, 1813. Bisshopp played an ancillary role in the British victory at Beaver Dams on June 24, 1813. An American prisoner wrote about Bisshopp, stating he was a “mild, humane-looking man of about 36 years of age (he was actually 30), rather tall and wellmade and a man of exceeding few words”.

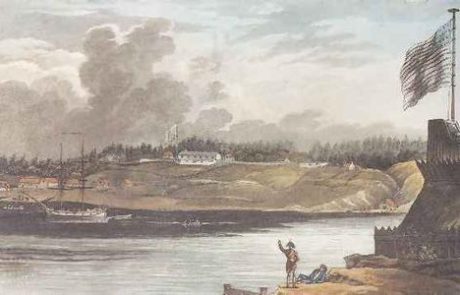

Emboldened by past triumphs, and in retaliation for the destructiveness of the American journey from Fort Erie and the occupation of Fort George, Bisshopp began thinking of raiding across the Niagara River into American territory in hopes of softening up the American resistance enough to dislodge their associates from Fort George and send them in support of beleaguered allies across the river. With this purpose, on the afternoon of July 10, 1813, Lt. Col. Bisshopp left his headquarters at Lundy’s Lane with 20 men of the Royal Artillery, 40 from the First Battalion 8th King’s Regiment, 100 of the First Battalion 41st Regiment, 40 from the 47th Regiment of Foot and 40 of the Second and Third Regiments of Lincoln militia, commanded by Lt. Col. Clark, who joined Bisshopp at Chippewa, creating a force totaling 240 men. This combined group crossed the Niagara River from Chippewa in six scows early in the evening, circumnavigating Grand Island in the Chippewa Channel, allowing them to remain unobserved from the American side and just before dawn on July 11, 1813, landed on the opposite shore at the point where Ferry Street (now Amherst Street from 1853) meets Niagara Street. They moved quickly to attack the blockhouse nearby and the enlarged earthworks embankment known as Fort Tompkins, manned by less than 12 artillerymen and 50 militia under American Maj. Adams reinforced with two or three pieces of cannon artillery. At the village of Buffalo two miles south were 100 infantry and dragoon recruits on their way to Fort George and a small body of Indians under Henry O’Ball, the young Cornplanter, who by now had renounced Western ways and returned to his native culture. Gen. Peter B. Porter had narrowly escaped capture in his own house, fleeing in his night clothes and later in a borrowed outfit gathered up in Black Rock some 200 militia whom he led south to Buffalo.

Bisshopp, accompanied by Col. Warren, had surprised Maj. Adams camp and he and his 50 militia moved south to Buffalo in such haste as to leave two intact artillery pieces unused on the ground to be taken by the British. Gen. Porter made an unsuccessful attempt to reach Adams camp, which by now had been deserted. The garrison at the blockhouse disappeared also with the building torched. Advancing on foot toward Buffalo, Gen. Porter met Capt. Cummings with 100 regulars advancing to Black Rock. In the meantime, the British not only fired the blockhouse and the deserted barracks, but attacked the naval yard and a schooner tied up at this mouth of the Scajaquada Creek once also defended by Maj. Adams’ 50 militia. Adams had been previously stationed at Fort Gibson from where he was dispatched to defend Black Rock with insufficient forces. The British officers now went to Porter’s still standing house where they ordered breakfast from the few servants remaining. Their troops and reinforcements constantly coming over from Canada plundered the public stores not yet destroyed by fire. Taken from these were pork, tobacco, flour, salt, corn and whiskey – the staples of most meals of the day. Bisshopp’s men then raided the warehouses at the naval base, spiking two 12 pound cannon and two 16 pound guns at the batteries on Scajaquada Creek, took another 12 pounder, two 9 pounders, 177 muskets, two kegs of ammunition powder, 250 pounds of round shot and canister shot, a large amount of Army clothing, seven large bateaus and a scow, with the latter ships being loaded with 180 barrels of preserved food provisions . The British burned the storehouses, blockhouse and barracks at both batteries, the rest of the naval yard, an unfinished schooner and in leaving, the rest of Black Rock not yet burned.

By this time, in Buffalo, Gen. Porter composed a force of 60 regular US Army under Capt. Cummings, 90 men from Maj. Adams garrison, 50 Buffalo militia under Capt. Bell and 30 American allied Seneca and Tuscarora warriors, totaling 230 men, plus a cannon fieldpiece. Porter planned a three pronged counterattack, with the Indians flanking Black Rock to the east through the woods along trails they had established and scouted before. The American forces ambushed Bisshopp’s columns in the dark as they marched along the beach on the way back to their boats. The British had not expected any further American response and were taken unawares. After a sharp skirmish, the British suffered many casualties and retreated to the point of their original landing. (In an earlier 1820s version, the British reached their boats intact, but with the stolen whiskey proving too much of a temptation, partied all night, leaving them in no shape to counter the sudden surprise American attack at dawn on July 12, 1813.) In both versions, as the British scrambled into their boats and pushed off, the Americans under Gen. Porter kept shooting into the British ranks as they began their river crossing. The British would have left earlier, save for a delay to await the column end loading of 23 barrels of salt, scarce in Upper Canada at the time. In the continuing furious action, the British suffered the loss of many more men, including the mortal wounding of Lt. Col. Bisshopp. Despite this, the British recrossed the Niagara River with most of their personnel and loot intact, leading this battle to be recorded by history as a British victory, although a pyrrhic one as Bisshopp had taken three gunshot wounds, sufficient to cause his death from blood poisoning and shock five days later on July 16, 1813. He was buried in Lundy’s Lane cemetery in a carved stone burial box under a stone cover engraved with his biography.

The British suffered three killed, 24 wounded, including Bisshopp, 13 captured and six missing The Americans had three killed, six wounded, and ten captured. The muskets of the day were notoriously short range and inaccurate. History records this as a British victory.

Excerpted from: “The Documentary History of the Campaigns Upon the Niagara Frontier From June to August of 1813” – 1971 by Ernest Cruikshank Part II, Pp. 218, 223 – 228. With attributes from the pamphlet (“John Bull – Patriots”) August 4, 2011