by Warren Glover

Brig. Gen. George McClure was commanding the New York State militia defending Fort George, captured earlier in Upper Canada, in 1813. He then decided to abandon this post on December 10, 1813, as harsh winter conditions were setting in, provisions were running low and no reinforcements were about to arrive. At this point, he ordered the neighboring village of Newark (now Niagara-On-The-Lake) destroyed by fire, even though it had no military value to either side. The inhabitants were given little advanced notice so they could prepare adequately to leave in view of the prevailing weather conditions. Instead, they were turned out ill-clothed and ill-provisioned into the cold winter’s night and all but one of the town’s 150 buildings were burned to the ground. This led to a high civilian casualty rate.

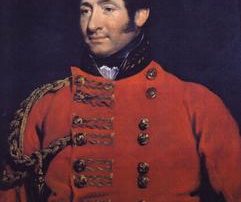

Prior to the battle, the opposing forces were at the following personnel and weaponry strength levels: British Maj. Gen Riall commanded 370 men in the First Battalion, First Regiment (Royal Scots), 240 of the First Battalion, 8th King’s Regiment, 250 of the 41st Regiment, 55 of the Light Infantry Company of the Second Battalion, 89th Regiment, 50 of the Grenadier Company of the 100th Prince Regents County of Dublin Regiment, 50 Canadian militia, and 400 native Americans allied to the British, totaling 1,415 officers and men.

The American commander was Maj. Gen. Amos Hall of the New York State militia, controlling volunteers and militia. Stationed in Buffalo were 129 cavalry under Lt. Col. Seymour Boughton, 433 Ontario county volunteers, under Lt. Col. Blakeslee, 136 Buffalo militia, under Lt Col. Cyrenius Chapin, from the corps of former Canadians as volunteers, under Lt. Col. Benajah Mallory, 382 of the Genesee militia regulars under Major Adams, who fled earlier from Bisshopp’s invasion and 307 Chatauqua militia under Lt Col. John McMahon. At Black Rock were 382 of Lt Col. Warren’s and Lt. Col. Churchill’s regiments under Brig. Gen. Timothy Hopkins, 37 mounted infantry under Capt. Ransom, 83 Indians under Lt. Col. Erastus Granger, and 25 militia/artillerymen with a six pounder gun under Lt. Seeley, for a total manpower count of 2,011 men.

Lt. Gen. Gordon Drummond, the newly appointed Lt. Governor of Upper Canada planned an offensive against the American positions on the Niagara Frontier in retaliation to the burning of Newark. In the early hours of December 18, 1813, troops under British Col. John Murray captured Fort Niagara by surprise from the American garrison, encountering fierce, but futile, late opposition from its otherwise prepared defenders. Another group under British Maj. Gen. Phineas Riall raided the American side of the lower Niagara River, burning the Villages of Lewiston, Youngstown, Manchester and the small nearby military outpost of Fort Schlosser. Riall’s excursions were eventually slowed down and halted respectively when the Tuscarora tribe intervened on the side of the fleeing civilian population of Lewiston and the Americans later set fire to the wooden bridge crossing Tonawanda Creek. At that point, Riall and men could not cross to go south and returned to the Canadian side and marched south around Niagara Falls, portaging their boats to Fort Erie.

The second, continuation of the battle commenced when Riall recrossed the Niagara River around mid- night on December 29, 1813 and landed with all of his men two miles downstream of Black Rock, where present day Amherst Street intersects with present day Niagara Street, at dawn on December 30, 1813.He delegated Lt. Col. John Gordon of the Royal Scots to land in Black Rock in order to attack the Americans from different directions . Maj. Gen. Amos Hall was first alerted to the British presence when Riall’s advanced guard, the light infantry company of the 89th Regiment, drove off the American pique at Conjockety, present day Scajaquada Creek and captured the bridge and the battery there. The Americans assumed the British would not return and so did not secure this area. Hall sent the militia under Churchill to reconnoiter. When he ran off at the first enemy gun fire, Hall dispatched a second force under Maj. Adams and Lt. Col. Chapin, who also ran off at the first sight of the enemy. Hall now took personal command of the remainder of his troops, ordering a detachment under Lt. Col. Blakeslee to attack the British left flank and then Hall advanced toward Black Rock with the rest of his men.

The second, continuation of the battle commenced when Riall recrossed the Niagara River around mid- night on December 29, 1813 and landed with all of his men two miles downstream of Black Rock, where present day Amherst Street intersects with present day Niagara Street, at dawn on December 30, 1813.He delegated Lt. Col. John Gordon of the Royal Scots to land in Black Rock in order to attack the Americans from different directions . Maj. Gen. Amos Hall was first alerted to the British presence when Riall’s advanced guard, the light infantry company of the 89th Regiment, drove off the American pique at Conjockety, present day Scajaquada Creek and captured the bridge and the battery there. The Americans assumed the British would not return and so did not secure this area. Hall sent the militia under Churchill to reconnoiter. When he ran off at the first enemy gun fire, Hall dispatched a second force under Maj. Adams and Lt. Col. Chapin, who also ran off at the first sight of the enemy. Hall now took personal command of the remainder of his troops, ordering a detachment under Lt. Col. Blakeslee to attack the British left flank and then Hall advanced toward Black Rock with the rest of his men.

As dawn broke, Hall directed a very heavy fire of cannons and musketry at Gordon’s Royal Scots, as they tried to land at Black Rock. Gordon was supported by the fire from a five gun battery, but three of his boats grounded at the last minute and his regiment took substantial casualties before they forced their way ashore. Riall now advanced with his main body against Hall’s center, sending a detachment from his left wing to hit the vulnerable American right flank. Although the Americans fought with obstinacy, after one-half hour of intense combat, the American right wing broke and was routed. In order to avoid being outflanked, Hall ordered a general retreat. The British pursued Hall all the way to Buffalo, two miles away, where his forces dissipated. Once in the Village of Buffalo, the British and Indians looted it and burned down all but four of its buildings. British troops destroyed the naval yard for the second time that year, plus three armed schooners being refitted (the Chippewa, the Ariel, the Little Belt) and one sloop (the Trippe). Riall’s force then moved on to Black Rock proper, where all but one building was razed to the ground. They then crossed undisturbed back over the Niagara River to Canada, taking loot and whatever dead and wounded they could find with them.

The British casualty return was 25 regulars, 3 militia, and 3 Indians killed, 63 regulars, 6 militia and 3 Indians wounded, and 9 regulars missing, for a total of 31 killed, 72 wounded and 9 missing. Of these, 13 killed, 32 wounded and 6 missing were from the Royal Scots, who endured a heavy cannonade while grounded in their boats. The Americans took five prisoners.

The official American casualty figures were 50 killed, 52 wounded. The dead included Lt. Col. Boughton. The Ontario Messenger newspaper of January 25, 1814, published a list of 67 Americans captured, 11 of whom were wounded. Lt. Col. Chapin was among the captured, along with eight pieces of American artillery. History records this battle as definitely a British victory. Normally, battles at this time in history would not be fought in winter, but it is testimony to British anger at the way its people at Newark were treated that the British launched their campaign immediately after, in midwinter.

On January 22, 1814, Lt. Gen. Sir George Prevost, British Commander-In-Chief for North America issued a letter to the Americans in which he expressed his regrets that “the miseries inflicted upon the inhabitants of Newark” had necessitated such appropriate retaliation.

General References:

Ernest Cruikshank 1908-republished 1971 “The Documentary History of the Campaigns Upon the Niagara Frontier in 1812 to 1814”, vol. 9. December, 1813 to May, 1814. New York Arno Press, Inc. Pp. 70, 71, 73, 74, 79, 88, 93, 96. Lt. Col. Joseph H. Eaton 2000 “Returns of the Killed and Wounded in Battle or Engagements With Indians, British and Mexican Troops 1790 to 1848” (Eaton’s Compilation) Washington D. C. National Archives and Records Administration. Microfilm Pg. 16. Robert S. Quimby 1997 “The U.S. Army in the War of 1812 – An operational and Command Study”, East Lansing, Michigan. Michigan State University Press. Pp. 355, 358, 359, 360.

Black Rock Navy Yard image by Peter Rindlisbacher can be purchased as a print in different sizes at: discover1812.com